WHAT ARE THE IMMEDIATE EFFECTS OF EXERCISE ON THE HEART?

Understanding how the heart initially responds to exercise can provide clues into the biological basis of various cardioprotective mechanisms.

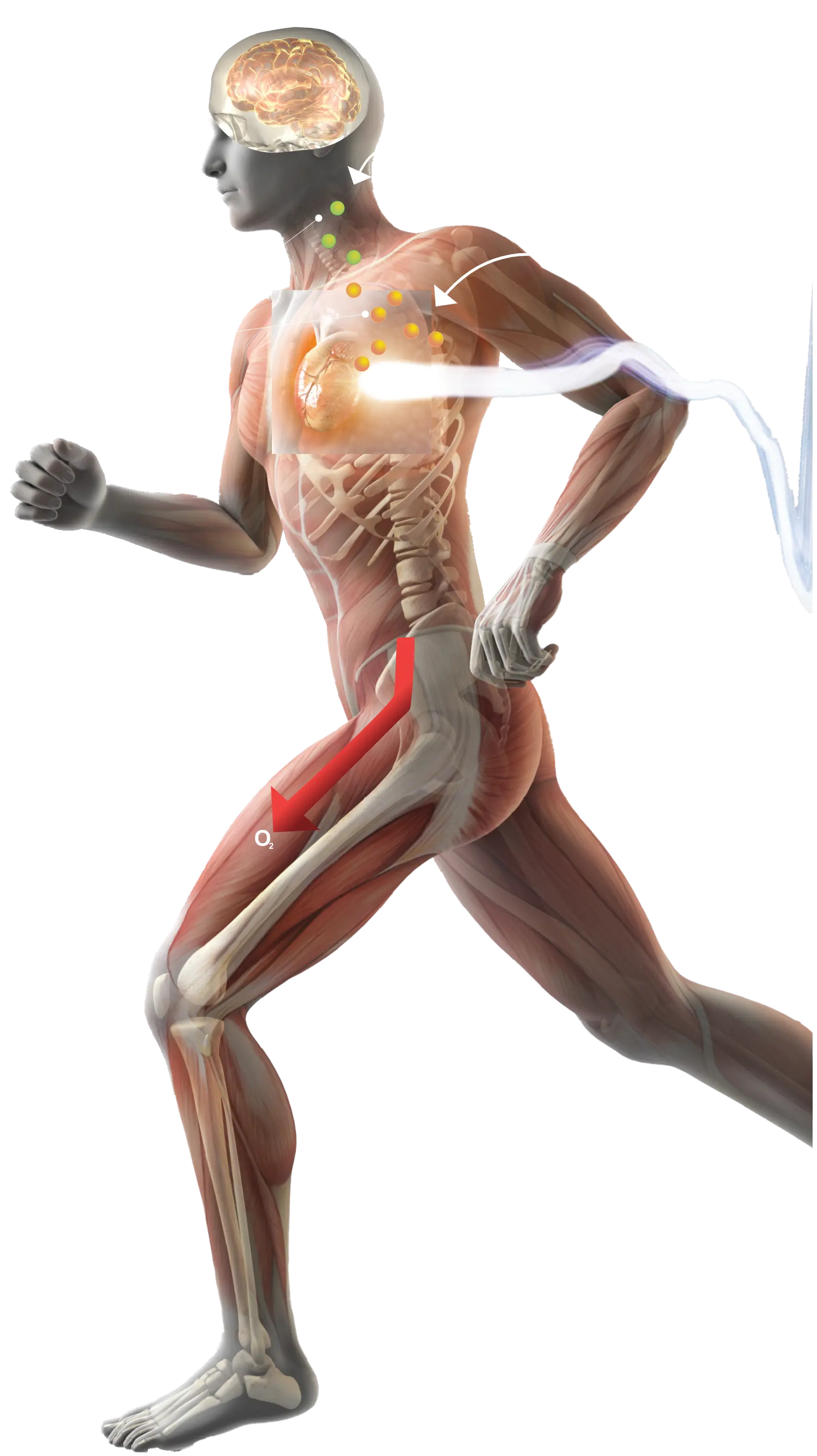

Many effects of exercise on the body emerge gradually. While runners slowly build stamina, their hearts register and react to physical exertion in real time. To satisfy the body’s changing needs and respond to increased stress during exercise, the heart experiences several immediate adaptations at organ, cellular, and subcellular levels. These short term effects help fuel the body during exercise and influence how it functions at rest, leading to lasting cardiovascular benefits.

How does the heart work?

While the runners stretch to warm up their muscles, their hearts perform the critical function of pumping blood throughout their bodies. This process occurs through a highly synchronized transfer of blood between four chambers: the right atrium, the right ventricle, the left atrium, and the left ventricle. The right atrium receives oxygen-poor blood from the body and pumps it into the right ventricle, which sends it through the pulmonary artery to the lungs. The left atrium receives the oxygen-rich blood from the lungs and pumps it into the left ventricle, which sends it out to the body through the aorta. As these four chambers work in concert, a system of structures that transmit an electrical signal acts as their conductor, cueing muscles in different chambers to contract and pump blood (1,2).

The electrical signal originates in the sinoatrial node, a structure in the right atrium that serves as the heart’s pacemaker. The electrical pulse travels through the atria, where it spurs the atria to contract and pump blood into the heart’s ventricles. The electrical signal then reaches the atrioventricular node, another structure near the center of the heart, and slows to allow the ventricles time to fill with blood. Then the atrioventricular node sends the signal through the bundle of His, a group of fibers that branches off into right and left bundles, forming a thread like network along each side of the heart. The electrical signal journeys through this network, causing the ventricles to contract and pump blood out of the heart (1,2).