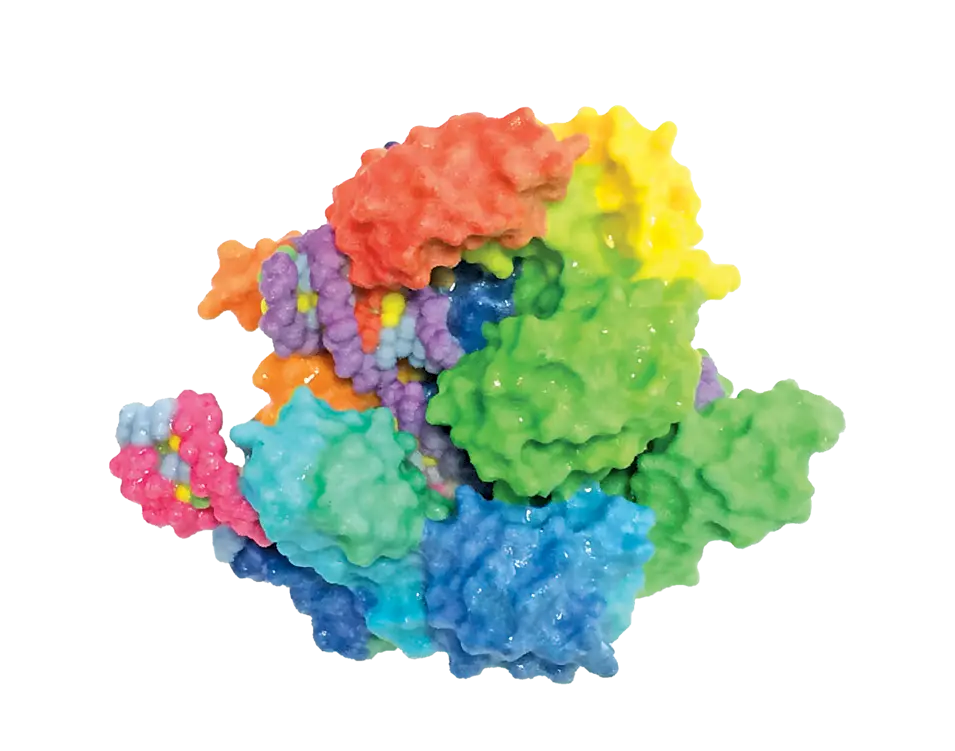

Following Mojica’s discovery of CRISPR, other scientists quickly identified Cas9, a protein that they predicted to cut DNA, in 2005. They also noticed that the spacer sequences in between each CRISPR repeat shared a short common sequence at one end, which they later termed protospacer adjacent motifs (PAM) (3).

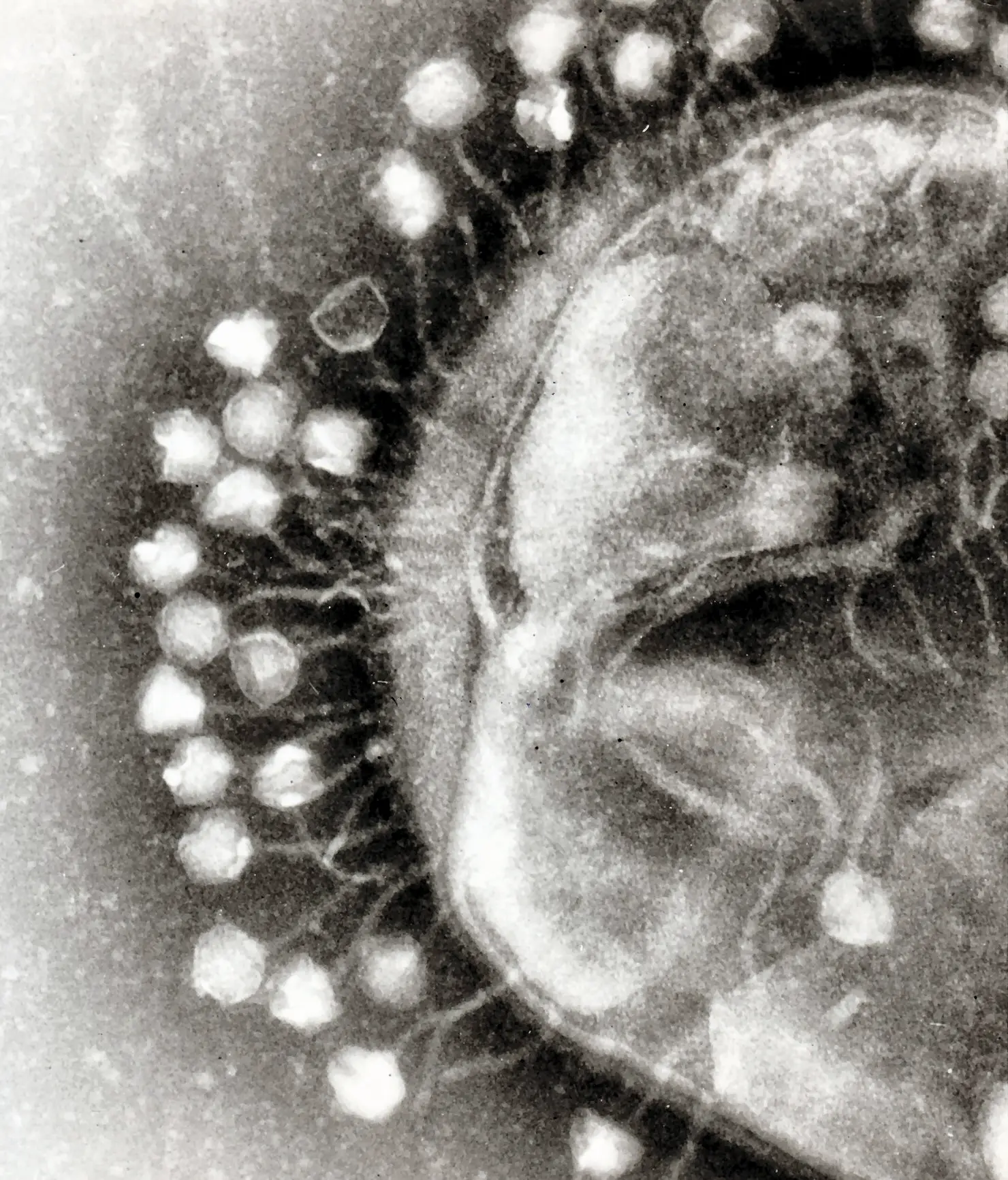

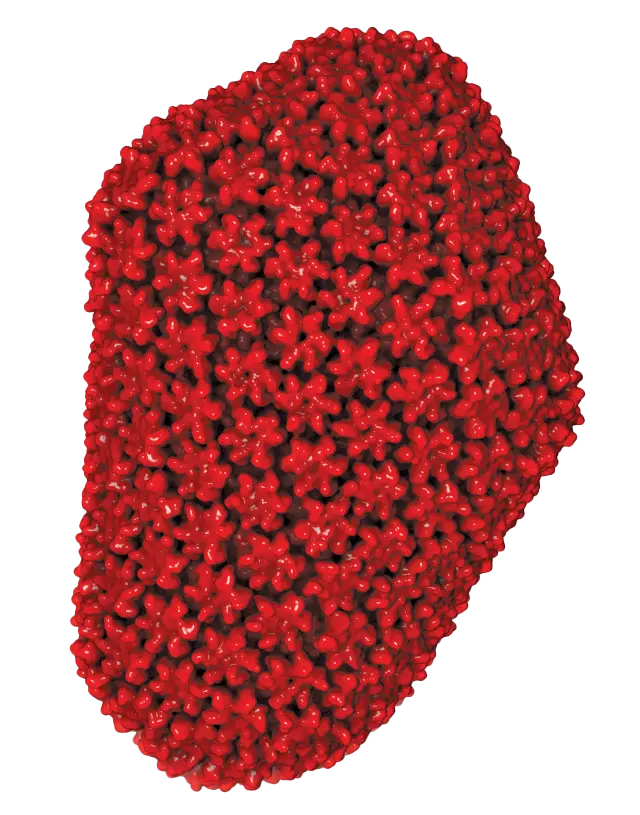

While several scientists had predicted that CRISPR-Cas9 was part of a novel DNA repair system, computational biologist Eugene Koonin at the National Center for Biotechnology Information took a different view. Koonin’s team was interested in horizontal gene transfer — the movement of genes between organisms of the same generation, rather than between parents and children — between different kinds of bacteria and archaea. Through computational analysis, he and his team confirmed Mojica’s finding that sequences in the spacers were shared by phages.

Based on these observations, Koonin’s team developed “a detailed hypothetical scheme of how this thing was supposed to work in adaptive immunity,” he recalled. He also drew potential parallels between CRISPR-Cas9 and RNA interference, where RNA molecules silence expression of certain genes, including those of invading viruses. This adaptive immunity hypothesis, published in 2006 (4), prompted molecular biologist Philippe Horvath, then at Danisco France SAS, to experimentally demonstrate that the CRISPR-Cas9 system provided resistance against phage infection in bacteria (5).

Erik Sontheimer, an RNA biologist then at Northwestern University, was also intrigued by Koonin’s proposed schema of the CRISPR-Cas9 role in adaptive immunity. Together with graduate student Luciano Marraffini (now at Rockefeller University), he set out to determine whether CRISPR-Cas9 targeted DNA or RNA (6).

One of his key experiments incorporated a spacer region into a plasmid containing a non-coding region of DNA, which he introduced into cells in culture. If CRISPR-Cas9 targeted RNA, no interference would occur since the spacer would not be transcribed into RNA. “Yet, we still had CRISPR interference,” Sontheimer explained. “The fact that we got CRISPR interference against the plasmid, even with a region that had no function and didn’t code for anything — that’s most consistent with DNA targeting.”