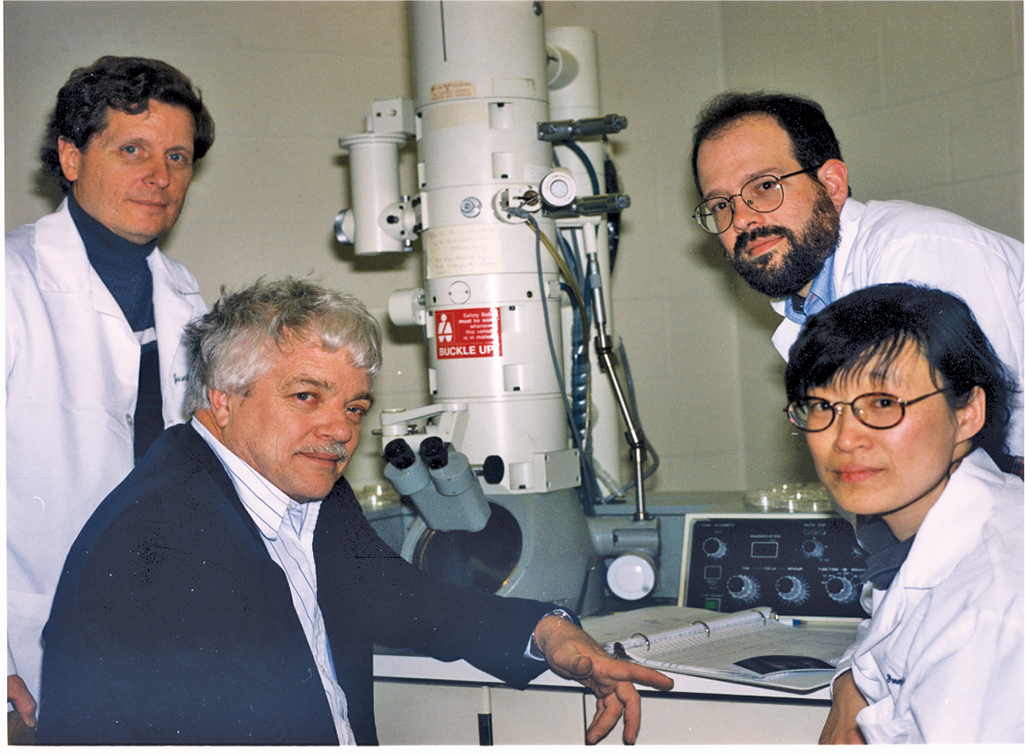

Just a few miles away, John Schiller, a molecular biologist, and David Lowy, a clinician scientist at NCI were exploring how to leverage the intrinsic self-assembling ability of HPV. “By this time, it was ten years since Hausen and his group discovered HPV in 50 to 70 percent of cervical cancers, and there really had been no progress in vaccines,” said Schiller. Neither he nor Lowy had any virology or immunology training, but they were interested in how viruses caused cancer.

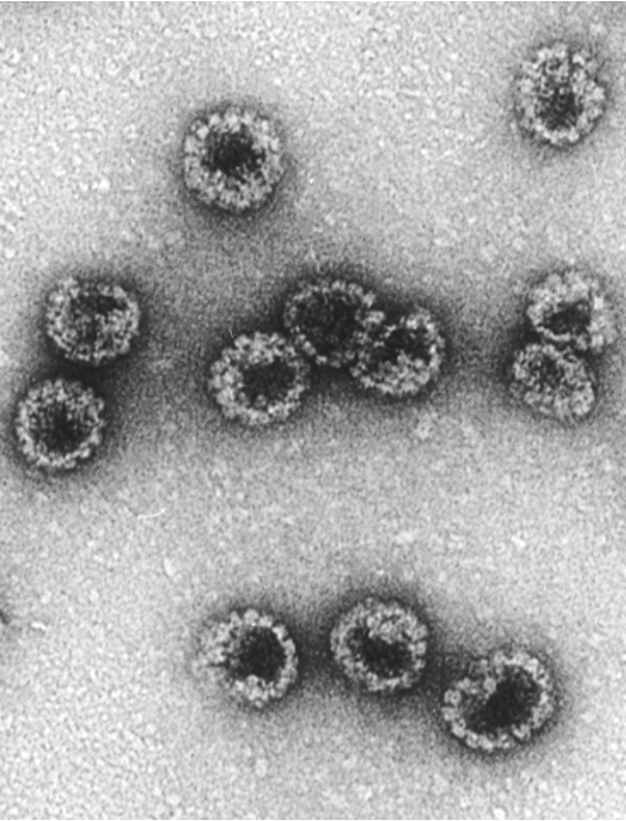

To develop an HPV vaccine, they needed to exclude the two genes, E6 and E7, that made the virus carcinogenic. Using VLP would allow them to assemble just the viral shell, which should stimulate an immune response without introducing the full viral genome. With the goal of a vaccine in mind, they infected insect cells, which met regulatory approval for use in clinical trials and could produce proteins at manufacturing levels, with a virus carrying the bovine papillomavirus L1 gene. Using electron microscopy, they observed L1 VLP produced by the cells.

They then eagerly took the crude cell extracts and injected them into rabbits to see if they could elicit an immune response. After diluting rabbit blood samples, they saw high levels of neutralizing antibodies (9). “Nobody sees neutralizing titers of 10,000-fold for any virus in an in vitro assay. We got titers like that, but we didn’t even have any real preparation,” said Schiller.

Yet, when they tried the same experiment using HPV, they got almost no VLP. Perplexed, they repeated the experiment using rhesus macaque papillomavirus and observed clear particles. “Unbeknownst to everybody, the strain that everybody was using, which was originally from Hausen, came from a cancer sample that had a mutation in the L1 gene, so that it almost couldn’t assemble,” said Schiller. He and Lowy cracked the case when they produced HPV L1V LP that elicited high titers of neutralizing antibodies using virus collected from patients with productive infections, not advanced cancer (10).